The first biography of the Beatles as a group appeared in the late 1960s. Written by English journalist Hunter Davies, The Beatles is an authorized biography, which means that Davies was obligated to get approval from the members of the band and other interested parties before the initial publication. The volume has since been revised and updated, and the 2009 edition includes an introduction by Davies, in which he details how this agreement affected the contents of the book. Davies reveals, for example, that Beatles manager Brian Epstein had given permission to disclose that he was homosexual, but Epstein died before the biography appeared in print, and his parents forbade mention of Epstein’s sexual orientation. In addition, John Lennon’s aunt, Mimi Smith, who had raised John as her son, objected to Davies’s depiction of John’s childhood, so Davies had to make changes. Davies’s introduction also reveals that he jotted down general impressions rather than employing a tape recorder, and that he made a number of other mistakes—for example, the vital first meeting of John and Paul at the Woolton Parish Fete occurred on July 6, 1957, not June 15, 1956, as Davies states. He did not correct these for the book’s reissue, preferring to preserve it as a work “of its time.” Despite its numerous flaws, however, The Beatles remains an important source for scholars. Based largely on interviews with band members and those in their inner circle, the book provided all future biographers with precious primary source information and acquainted readers with the major details of the Beatles’ humble beginnings. Equally important, the very publication of a biography of the Beatles lent credibility to the Beatles as artists and not just teen idols—thus opening the door for further examinations of the group’s lives and recordings.

A decade later, Nicholas Schaffner’s The Beatles Forever broke a long fast for Beatles fans eager to learn more about the group than was available in sketchy accounts offered in magazines. A musician and journalist, Schaffner provides a brief biographical overview of the band from an American fan’s perspective. The text is complemented by hundreds of photographs, many of them examples of the then-burgeoning memorabilia associated with the Beatles. The book’s discography and extensive bibliography were among the first on the Beatles to appear in print. Philip Norman’s Shout! The Beatles in Their Generation, an important expansion of Davies’s biography, casts a more objective eye on the group. By this time, the band had acquired legendary status, and rumors and unsubstantiated stories abounded. Tempering his obvious enthusiasm for the Beatles by acknowledging their human frailties, Norman offers insight into their popularity, artistry, and impact on their peers. Though Norman relies heavily on Lennon’s notoriously unreliable aunt, Mimi Smith, for his account of Lennon’s childhood, the book is engaging, readable, and still widely hailed as one of the definitive biographies of the group.

Of the dozens of books devoted to the group in the 1980s and 1990s, Bob Spitz’s The Beatles: The Biography is by far the most thorough and scholarly biography to appear. At more than 900 pages, Spitz’s biography is twice the length of Norman’s book, and it includes 854 endnotes. Spitz had previously written an acclaimed biography of Bob Dylan (Dylan: A Biography, McGraw-Hill, 1989), so he was no newcomer to the genre. The Beatles took him eight years to research and write, and fans and scholars alike appreciated the effort. The strength of the book lies in its examination of the early years of the band and in Spitz’s willingness to shed the image of the Beatles as “good boys.” He spares no details in bringing to light many of the less-than-lovable characteristics of the band, which was once styled as a counterpart to the bad boys of rock, the Rolling Stones. And Spitz leaves little doubt that Yoko Ono sowed the seeds of the Beatles’ demise. He portrays Ono as determined to gain control of John Lennon, a view held by many. Another excellent biography is Jonathan Gould’s Can’t Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain, and America, a lengthy treatment that succeeds as both an entertaining look at the lives of the band members and as a scholarly treatment with a clear and important thesis: i.e., the former colony helped repay the formidable literary and cultural debt owed to the mother country. In contrast to Spitz, Gould conducted few interviews for the book and instead relied on the research of others. He goes well beyond conventional biography to show how the band revolutionized the popular culture of both their native England and the United States, which adopted the group as its own. Gould is less interested in the character flaws of the Beatles than in the positive vibe they brought to two countries in their eight-year recording period.

As good as Gould’s book is, the first volume of Mark Lewisohn’s All These Years gives evidence that this the three-volume set will be the most comprehensive, accurate, and thorough biography of the group available. Published in 2013, the first volume (bearing the volume title Tune In), which covers the band’s beginnings, concludes on the eve of 1963, which was to be the Beatles’ annus mirabilis. In addition to dispelling many longstanding myths and correcting dozens of factual mistakes in earlier biographies, Lewisohn provides detailed profiles of those vitally important to the Beatles’ success, notably manager Brian Epstein (1934–67) and producer George Martin (1926–2016). No significant biographical detail is left uncovered, and Lewisohn provides an excellent account of the music scene the Beatles revolutionized. Lewisohn is the only professional, full-time Beatles scholar, and his devotion to the group and the research process is on full display throughout the book. The first volume of this detailed account of the band’s career is a godsend for true fans and scholars. Even those already familiar with the lives of Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr will discover new facts on nearly every page. Those who study and love the Beatles eagerly await the next volume in the set.

In addition to biographical treatments of the Beatles as a group, numerous titles document the lives of individual members of the band. That John Lennon has attracted more biographers than any of his bandmates is not surprising. His was a tragic and tumultuous life. Raised by his aunt after being abandoned by both his mother and his father, Lennon was forever psychologically scarred. Rock ‘n’ roll gave his life much-needed direction, but he never truly came to terms with his demons. Lennon’s post-Beatles life was similarly fraught with personal problems and included run-ins with the FBI after he moved to New York. Of the books written by those who knew him personally, the most interesting are those by his childhood friend Pete Shotton and by his first wife, Cynthia Lennon. Shotton remained friends with Lennon after he became famous, and his firsthand accounts of Lennon in John Lennon: In My Life, coauthored by Nicholas Schaffner, as bossy boy, troubled adolescent, and famous star are revelatory. Cynthia Lennon wrote two accounts of her life with John: A Twist of Lennon and John. Though the first is interesting, the second is superior. In it she writes openly of all sides of Lennon, pulling no punches. This engaging account ends with the chilling statement that if she had known all that lay ahead when she first met John, she would have walked away from him.

The first work by a professional biographer to appear after Lennon’s death was Ray Coleman’s two-part biography, issued as separate volumes: John Winston Lennon (covering 1940–66) and John Ono Lennon (covering 1967–80). These complementary books provide a solid overview of Lennon’s life as a Beatle and solo artist. Coleman is largely sympathetic to his subject. By contrast, Albert Goldman’s The Lives of John Lennon has been described by many fans and more than a few reviewers as character assassination. Goldman paints a picture of John as a puppet controlled by Yoko Ono, a man who had completely lost direction and control of his life by the time the group disbanded. The author includes a mass of sordid details gleaned from more than a thousand interviews. After Lennon’s death in 1980, some accounts of his life veered toward hagiography; Goldman’s diatribe more than redressed this imbalance. Though many disregard the entire book, Goldman did uncover some new truths about Lennon, so the book—though strewn with factual errors and unsubstantiated allegations—is not entirely without merit. Philip Norman’s John Lennon: The Life is more levelheaded. In his previous work on the band (mentioned above), Norman betrayed his interest in Lennon by stating that he was “80% of the Beatles.” The book is more a biography of the man than the musician: Norman is particularly good on how Lennon helped transform the class system in Britain, but he is less effective in describing the nature of Lennon’s creative gifts. Nor is he much interested in Lennon’s post-Beatles activities. In the end, the book is a solid piece of scholarship, sympathetic to Lennon but not fawning. Tim Riley’s Lennon: The Man, the Myth, the Music delivers on all three accounts. Though acknowledging Lennon’s many flaws, Riley focuses on what made him a remarkable musician and an important cultural figure. His description of Lennon as having “another kind of mind” sounds vague at first, but Riley fleshes it out gradually. Lennon’s turbulent life is difficult to convey clearly, but Riley succeeds where others have failed. Those seeking a balanced and analytical account of Lennon’s life and music will find Riley’s biography ideal. Other books are less ambitious, though some merit mention. Anthony Fawcett’s John Lennon: One Day at a Time: A Personal Biography of the Seventies is sympathetic to Lennon as a “practical dreamer” and concentrates on his solo years. Gary Tillery’s The Cynical Idealist: A Spiritual Biography of John Lennon addresses the musician’s largely unresolved thoughts on God. The author invokes psychiatrist Viktor Frankl in exploring Lennon’s struggles to come to grips with the meaning of his life and life in general. Francis Kenny’s The Making of John Lennon picks up on the theme of Lennon as a man attempting to come to terms with opposing forces within, positing that Lennon’s difficult childhood led to the creation of a “self-contradictory persona.” Anthony Elliott categorizes his The Mourning of John Lennon as a “metabiography,” an attempt to explore what the wide range of reactions toward Lennon revealed about society. This is an unusual approach, and Elliott largely succeeds in providing another way to view this complex man. Some sixty authors are anthologized in The Lennon Companion: Twenty-Five Years of Comment, edited by Elizabeth Thomson, and the fact that they represent a number of different countries and disciplines testifies to the fallen Beatle’s vast influence.

Though viewed by most as Lennon’s equal in terms of talent and importance to the band’s success, Paul McCartney led a much more conventional life and has attracted less interest among biographers. That said, his life has not been without significant challenges. Like Lennon, he lost his mother at an early age. And he was hit the hardest by the dissolution of the group in 1970. Though brief, Geoffrey Giuliano’s Blackbird: The Life and Times of Paul McCartney shows all sides of the man. Ross Benson’s Paul McCartney: Behind the Myth nicely portrays the artist’s relationships with his father, with Lennon, and with his wife Linda. Barry Miles’s Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now was the first truly important biography of McCartney and remains definitive, at least in its treatment of the Beatles years. Miles is an experienced biographer, having written books on Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, but he is also an intimate friend of McCartney, who granted him hundreds of hours of interviews between 1991 and 1996. Not surprisingly, the book is sympathetic to its subject. In some ways, Miles comes off as McCartney’s mouthpiece, and some have seen the book as McCartney’s effort to set the record straight and refute the belief that Lennon was the brains of the operation. Nevertheless, Miles paints the most detailed picture of McCartney as Beatle, especially his relationship with producer George Martin. Miles also discusses McCartney’s involvement with London’s avant-garde scene in the late 1960s. Though the book sketches McCartney’s solo years only in a brief afterword, other titles cover that period of McCartney’s life. For example, in Man on the Run: Paul McCartney in the Seventies, Tom Doyle effectively explores McCartney’s initial struggles after the 1970 breakup and ultimate triumph as the decade progressed. Peter Carlin and Howard Sounes cover McCartney’s entire solo career with varying degrees of success. Carlin’s account, Paul McCartney: A Life, is breezy and breaks little new ground. But though it draws too heavily on Miles to be of much interest to scholars, it has value for those interested in a straightforward biography. In his comprehensive Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney, Sounes devotes equal space to his subject’s Beatles and solo years. Sounes is refreshingly opinionated and covers all aspects of McCartney’s personality. In the end, those wishing to get the full picture of McCartney will be best served by relying not on a single account but on three: Miles on McCartney’s years as a Beatle, Doyle on McCartney’s struggles to establish himself as a solo artist, and Sounes on McCartney from 1980 to 2010.

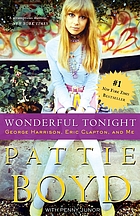

George Harrison attained great fame as a Beatle, but he came to find that fame wanting. His interest in Indian music led him to explore Eastern spirituality, and his life after 1965 can be seen as a struggle to renounce the material world and concentrate on matters of greater import to him. When it broke in 1980, the news that Harrison would write an autobiography, the first by any member of the group, raised great hopes among fans and scholars. First published as a limited edition, and subsequently by Simon & Schuster, that book, I, Me, Mine, proved to be a disappointment. But while it is a snack rather than a meal, it is straight from the mouth of the musician. Although a surprising number of biographers have explored Harrison’s life, they differ in focus, and no one book stands out. Joshua Greene and Gary Tillery concentrate on his spiritual side in, respectively, Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison and Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison. Though they provide few genuine insights into Harrison the man, Alan Clayson’s The Quiet One, Dale Allison’s The Love There That’s Sleeping, and Marc Shapiro’s All Things Must Pass capably cover both Harrison’s beliefs and his music. Even better is Ian Inglis’s similarly themed The Words and Music of George Harrison. Graeme Thomson’s George Harrison: Behind the Locked Door is the most complete and recent biography. Pattie Boyd, Harrison’s first wife, offers her memories in the entertaining (albeit slight) Wonderful Tonight: George Harrison, Eric Clapton, and Me (written with Penny Junor). Olivia Harrison, his second wife, contributes George Harrison: Living in the Material World, edited by Mark Holborn (a companion to Martin Scorsese’s 2011 film by the same title); it combines photographs and some text and includes an introduction by Paul Theroux and a foreword by Scorsese.

It is not surprising that only two biographies of the group’s least heralded member, Ringo Starr (born Richard Starkey), have appeared. Starr’s skill as a drummer was discounted for a number of years, but recently his reputation has been restored. Although his work was integral to the Beatles sound, few have seemed interested in writing a book-length treatment of his life. For anyone so inclined, both Ringo Starr: Straight Man or Joker? by Alan Clayson and Ringo: With a Little Help by Michael Starr (no relation) are fine. The latter is more complete and up-to-date.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the inner circle—in particular, manager Brian Epstein—to the Beatles and the eventual success they enjoyed. Epstein took four talented but sloppy and unprofessional young men and transformed them into a tight outfit fully able to realize their abilities in the world of professional music and entertainment. Epstein’s memoir, A Cellarful of Noise, though bland, is worth noting. For better insights into Epstein’s personality, readers will want Lewisohn’s All These Years (discussed above) or Ray Coleman’s The Man Who Made the Beatles: An Intimate Biography of Brian Epstein. Alan Williams, who managed the group before Epstein did, discusses the early days of the band in The Man Who Gave the Beatles Away.

The Beatles were isolated during their years of fame. They trusted few to guard their privacy and keep their secrets. However, after the band broke up, a number of the inner circle published books about the group. Though none of those books is particularly remarkable, a few deserve mention. Tony Barrow was one of the first in the music industry to publicize the Beatles, and he subsequently became close to members of the group. His John, Paul, George, Ringo & Me, edited by Julian Newby, makes good reading and is especially useful for those interested in the band’s first few years of success. Peter Brown, who was a personal assistant first to Brian Epstein and then to the Beatles, cowrote (with Steven Gaines) The Love You Make: An Insider’s Story of the Beatles. Alistair Taylor, known to the Beatles as Mr. Fixit, held a position similar to Brown’s. His Yesterday: The Beatles Remembered, coauthored by Martin Roberts, is organized as a series of letters to an imaginary pen pal. Julia Baird (John Lennon’s half sister) wrote Imagine This, which formed the basis for a 2011 biopic on Lennon, Nowhere Boy. Astrid Kirchherr, a German photographer who met the Beatles in Hamburg in 1960, was the first of many to extensively photograph members of the group. While photo collections of the band abound and are normally not important to scholars, Kirchherr’s excellent When We Was Fab provides a look at their initial attempts to develop an image, before Brian Epstein changed their look.

Lennon: The Man, the myth, the music--the definitive life by

Lennon: The Man, the myth, the music--the definitive life by  The Cynical idealist: A Spiritual biography of John Lennon by

The Cynical idealist: A Spiritual biography of John Lennon by  The Making of John Lennon: The Untold story behind the rise and fall of The Beatles by

The Making of John Lennon: The Untold story behind the rise and fall of The Beatles by  Here comes the sun: The Spiritual and musical journey of George Harrison by

Here comes the sun: The Spiritual and musical journey of George Harrison by  Working class mystic: A Spiritual biography of George Harrison by

Working class mystic: A Spiritual biography of George Harrison by  The Love there that's sleeping: The Art and spirituality of George Harrison by

The Love there that's sleeping: The Art and spirituality of George Harrison by  Wonderful tonight: George Harrison, Eric Clapton, and me by

Wonderful tonight: George Harrison, Eric Clapton, and me by